EUGENE J. McCARTHY

By Keith C. Burris

originally published December 12, 2005 in the Journal Inquirer

GENE McCARTHY LED what was certainly the most refreshing and hopeful political campaign in my lifespan of 50 years, and maybe in the history of the nation.

For one brief, shining moment, idealism was not corny. Kids were in politics (it was called "the youth movement"). Ideas mattered. And a politician risked his political life because a cause was just.

The moment was very brief, and, as it turned out, fragile, much like John Kennedy's presidency, but it was a fine moment, and people who were there still get misty-eyed.

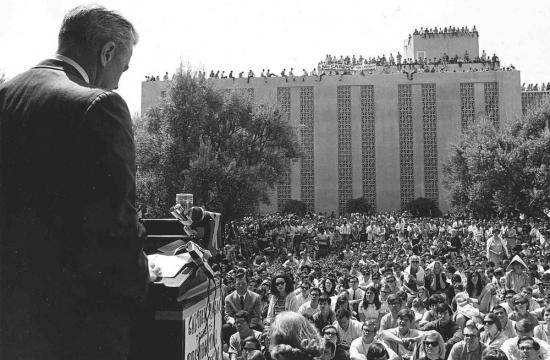

The campaign of Eugene J. McCarthy for the presidency in 1968 -- "the children's crusade;" the grassroots, almost spontaneous movement whose emblem was a red and purple dove of peace -- deserves to be remembered. It deserves an honored place in our past.

So does the man.

Actually, people do remember. It is history that seems a little vague.

I have seen, in recent years, history books and documentaries in which the withdrawal of Lyndon Baines Johnson from the race for the presidency in 1968 is treated as an act of nature -- as if the old guy just wanted to go home to Texas.

But some of us remember. And we had better write it down and hide it in an oak tree somewhere: Lyndon Johnson quit after Gene McCarthy stunned him in the New Hampshire primary and beat him in Wisconsin. LBJ returned to Texas like a wounded, half-mad Lear. And though the Democratic Party found a way to shut it down (tutored by LBJ and Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago), for a time American democracy seemed to be being reborn before us.

To walk through an airport with Eugene McCarthy, or to sit in a restaurant with him, especially in recent years, was an extraordinary thing. Thousands of Americans were last optimistic during that campaign, and for them McCarthy was a first, and last, hero. They would come up and say: "I just want to thank you. You gave me an honorable way to act. You made me believe in the decency of the nation." To witness these exchanges was very touching. National history became personal history. People related to a great national icon like a long-absent favorite uncle.

The kids of '68 are old men and women now, or nearly old. They saw McCarthy as an existential hero -- an inner-directed man who had not sold out, who had paid a political price but kept his head, and words, and thoughts high. And what they saw was true.

I suppose to walk down the street with Nelson Mandela in South Africa must be a similar experience. But imagine if Mandela or Vaclav Havel were but a footnote in the history books of his land.

Of course the shadow of the Kennedys hangs over the 1960s, which is not their fault. And civil rights. And the assassinations. But McCarthy apparently lived too long for history's first drafters.

While he still inspired aging hippies and associate professors, he became a relic to the cocktail set, a hero whose importance was uncertain in the minds of many -- the last idealist in the age of ultimate cynicism.

Blame the age.

I won't say Gene McCarthy never let down those who looked up to him. He was human. And all politicians do embarrassing things from time to time, either because they are trying to make a buck or are trying to regain the public eye. Look at the Clintons. Or Ronald Reagan working as a Las Vegas greeter after leaving the presidency. Or George Bush, the elder, as a bagman for the Saudis. McCarthy did some dumb things -- like endorsing Reagan in 1980 (defensible as a patriot, perhaps, but suicidal for totem Democrat). Or accepting the "Consumer Party" nomination to be president in 1988. He didn't take himself seriously enough. He didn't guard his own reputation. This, and occasional displays of vanity, were the things that could sometimes diminish him.

But, by and large, over 60 years, his judgments were sound, his insights profound, and his motives high. He dignified every room or debate he entered and he upgraded any company he kept. People looked up to him, not only for what he'd been, but who he was, not only physically but intellectually. I watched him with Bill Clinton, and George Herbert Walker Bush, and Tom Daschle, and Warren Beatty -- men of power and ego deferred to Gene McCarthy. I was with him on Capitol Hill on a few occasions and it was the same deal. Republicans and Democrats, young and old would seek him out: "Sir, I just want to shake your hand. I have always wanted to meet you."

Courage is perhaps the rarest thing in politics, so people in politics greatly, and often grudgingly, respect courage. McCarthy, as the song says, did it his way. He had almost absolute political courage, the way some musicians have absolute pitch. He was fearless. As one of his friends said, some years back: "He lived his values."

II.

The proper analogy for Gene McCarthy's later career is Norman Thomas. For him, politics was not office but vocation.

The proper context for his entire career is Catholicism -- radical, Midwestern, egghead Catholicism. McCarthy came from St. John's College in Collegeville, Minn., where he was briefly a Benedictine novice. He taught at St. Thomas College in St. Paul. He was a part of the Catholic Rural Life movement in the 1930s. He was a Catholic intellectual and writer. That's always who he was. Part of what made him different is that, though he could work a room like Frank Skeffington, essentially he lived inside himself.

He was less a liberal than a liberal Catholic. And part of what separated him from the Kennedy family was his brand of Catholicism. John Kennedy was a cultural Catholic. McCarthy was a social gospel Catholic. The Kennedy code, in politics, was: Win at any cost. McCarthy, said the poet Robert Lowell, was a "lost-cause man." His code was more like: Do justice. And failing that, at least muck up the power structure.

The theory of a St. John's Catholic education was, said McCarthy's old aide and pal Jerry Eller, "Read all the best stuff you can until you are 25, and then do something about it." Politics is a vocation. And you can't quit a vocation.

III.

A reviewer once remarked that it was a shame Gene McCarthy's poems did not carry with them the virtue of anonymity. It is also a shame that his 22-year record in the House and Senate is overshadowed by his 1968 campaign for the presidency, as well as subsequent campaigns. For McCarthy's career in Congress was quite a career.

In the House he was the leader of the liberals (though he was also considered a protege of Sam Rayburn's, and McCarthy dedicated one of his early books to the Speaker). The liberal band in the house in those days became known as "McCarthy's Marauders" or "McCarthy's Mavericks," and they left two legacies. First, the Mavericks evolved into the Democratic Study Group, which in turn became and remains the chief policy arm of the Democratic Caucus. Second, the original platform of the DSG, which was known as "McCarthy's Manifesto," became the basis of the civil rights legislation of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and of much the Johnson Great Society legislative agenda -- such things as open housing, student loans, and job training.

The fearlessness (some said recklessness) McCarthy showed in standing against Lyndon Johnson in 1968 was there, for anyone who looked, all along. Gene McCarthy debated Joe McCarthy. He opposed loyalty oaths. At the height of the red scare, he spoke up for the due process rights of those dubbed security risks in the government.

McCarthy's way in the Senate was rockier. After Lyndon Johnson's strong-armed leadership of that body (ending only with his vice presidency), senators were not interested in natural leaders or in being organized around principles or platforms. In the higher body, McCarthy's Marauders became a band of one. But McCarthy eventually chipped out a place for himself there, becoming the Senate's token intellectual and specializing in a few narrow problems and forward-edge issues. (A wag said that Phil Hart of Michigan was the conscience of the Senate in those days and McCarthy the mind, which meant that colleagues didn't have to listen to either man.)

McCarthy sat on the Finance Committee, where he focused on expanding Social Security coverage for those with disabilities and nudging the tax code toward progressivity in the era of Russell Long's chairmanship. On Foreign Relations, his other major committee, McCarthy began to lay out the rational, cost-benefit case against the Vietnam War, leaving it to William Fulbright to make the diplomatic case and Wayne Morse to make the legal one. McCarthy always figured the moral appeal would take care of itself.

He was the Senate's first champion of migrant workers and welfare mothers, bringing the latter to the Senate to testify on welfare reform. And when the Vietnam Veterans against the War came to Washington and camped on the mall, while other born-again doves spoke openly against the war for the first time at the vets' rallies, McCarthy sat by their campfires at night and listened to their stories. ("He just showed up one evening," said one, "wearing a windbreaker and carrying a six-pack.") He bought the vets a suite of hotel rooms so they could change clothes and shower. And there was no press release on that.

He was the first, and for many years the sole, sponsor of the Equal Rights Amendment.

He was a unique senator. Before Daniel Patrick Moynihan came to the Senate, Gene McCarthy used it as his classroom. Before there was Paul Wellstone, there was Gene McCarthy.

McCarthy made a huge mistake retiring from the Senate in 1971.

In 1976, running for president as an independent, he talked about chronic unemployment and the need for a shorter workweek, both to create work and expand leisure. He talked about the need to get Americans hooked on smaller, more fuel-efficient cars. He said that even if they did not destroy our environment we could not, as a society, afford our automobile addiction over the long haul. (He advocated a horsepower tax to encourage the transition to smaller cars.) He talked about militarism in foreign policy and the need to deregulate national politics and make it competitive. These ideas would have gotten more of a hearing if he had still been in the Senate, where he and his patriotic ideas belonged.

In 1982, he wanted to go back to the Senate. Minnesota Democrats were at first receptive, but then found a candidate with $10 million to spend on his own race, and they abandoned McCarthy again. Again, blame the age.

IV.

He will be remembered for 1968, of course. For the kids who went "clean for Gene"; "dumping Johnson"; and for an interlude of clarity and hope in a year of war and riots and killing.

Some of the speculation that has come since, and an excretion of a biography notwithstanding, McCarthy didn't want to run in '68. He was not truly the martyr type, though he tried to cozy up to Thomas More's writing and Robert Bolt's play about More. McCarthy knew what the cost would be and preferred not to end his mainstream political career. He didn't think he and his family were tough enough for what might come. (Mind you, this was before anyone was thinking about assassinations, a threat McCarthy also faced at a certain point in that crazy year.) And he was, at heart, a private, quiet man, uncomfortable with hero worship of any kind, but especially that which was directed at him. (McCarthy told Johnny Carson, in 1968, that he thought he would make an "adequate" president. It may have been the first time a politician caused the late-night king to break up.)

A sad thing for me is the alienation that set in between McCarthy and his party. It began with his reluctance to endorse Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and did not abate until John Kerry in 2004. McCarthy called Kerry "a good guy with some of Jack Kennedy's sense of nobility and service." McCarthy even attended a Democratic unity dinner during the '04 campaign.

I think the bad blood with Humphrey, and with the party as a whole, was a complex mix that was partly philosophical and partly personal. McCarthy came to feel the party had lost its soul and become an amalgam of ideological and avaricious interests, and that it had almost ceased to exist as a national organization, not to mention intellectual entity. And he simply didn't have much respect for Jimmy Carter or much personal connection to people like Mike Dukakis. Walter Mondale, McCarthy's former junior in the Senate, is a special case. That's also a complicated relationship.

To me, this divorce was tragic. The Dems needed McCarthy and he, after all, needed them. They needed his mind. He needed a political home. An effective third party, McCarthy's late-life near-obsession, is not going to happen. The Democratic Party, leaky vessel though it may be, is the only practical means by which to pursue McCarthy's lifelong aspiration: a greater measure of social justice, the security of our civil liberties, and a rational foreign policy for the United States.

V.

What is the legacy of Gene McCarthy?

I believe it is epic. To paraphrase the historian Douglas Brinkley, it is greater than some presidencies.

It is two huge things:

1) The people pick their leaders, not the boys in the back room. Not John Bailey. Not Mayor Daley. Not a departing, disgraced president.

McCarthy made the Democratic Party democratic.

2) In a democracy, the public, via the Congress, but not exclusively via Congress, has something to say about going to war.

Sadly, tragically, it takes much longer to stop a war than to start one. It took from 1967 to 1975 to stop Vietnam. But had it not been for Gene McCarthy, Vietnam would have lasted at least another five years.

And thanks to McCarthy, 18-year-olds can vote in this country. There were not enough of them voting to turn the election in 2004. But the youth vote was up by a million last year, and when it is up by 4 million, it will turn elections. Perhaps then it will be said that the nation finally went clean (or green?) because of Gene.

McCarthy also showed you can speak clearly and softly and have an impact. It isn't tried that often. But it ought to be. I notice John McCain does not bellow or yell, and he is the most popular politician in America.

As a campaign poster declared, "He stood up alone and something happened."

Is it also possible to run for president and be a complicated man with a complex view of life?

At the moment the answer would seem to be negative.

But the pendulum swings. John Kennedy was elected president, and so was Woodrow Wilson, and so was Abraham Lincoln.

Two of these presidents were also wits. I suppose the thing I most like to remember about McCarthy is his wit -- not just mischievous, but radical, deconstructing. America has always confused wit with jokes. Will Rogers was not in the same business as Jay Leno. But many of our greatest Americans were wits -- because wit comes out of the futility and absurdity and hope of life, and is based on an honest assessment of the momentary situation. Wit is a first cousin to courage. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Mark Twain, Franklin and Teddy Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, Clarence Darrow, and Frank Capra all had wit.

I think of McCarthy, in 1976, campaigning in Ohio. A tire blew on a car, we missed a plane, and so a press conference in St. Louis was scratched. The driver, my friend Karen, was in tears. "Don't worry," McCarthy said, as he put her arm on her shoulders. "When you are campaigning with me you can be sure it's never the worst thing that's happened."

I remember what he said about George Romney, who said he was "brainwashed" on the Vietnam War by LBJ: "I think, in George's case, a quick rinse would have done the trick."

Or what he said about Jimmy Carter: "He seems like a child lost in an airport."

I recall what he said to me when we went to Sunday Mass one day in New Hampshire during the presidential season. We were about 10 minutes early and the church, which looked like it held about 800, had roughly 40 people in it: "Looks like one of our rallies."

Or discussing the need for more fuel-efficient cars and the lack of need for an engine that will go 120 mph: "We could make cars that only go 60 mph but still equip them with speedometers that go to 120 ... The second half would be like the lust in Jimmy Carter's heart. A driver could just think about it."

* * *

Gene McCarthy is not a footnote in the great text of American history. He is a chapter -- an uncommonly noble one.

In his famous speech nominating Adlai Stevenson for president, McCarthy said two things that ring true about his own political life:

-- "His enemies said he spoke above the heads of the people. But they said it only because they didn't want the people to listen."

-- "He stood off the guerrilla attacks of his enemies and the sniping attacks of those who should have been his friends."

In 1968 Walter Lippmann said of Gene McCarthy: "The mission of Senator McCarthy is to do whatever a gifted and honest man can do to stop the rot in the American political system."

That is what he did.

* * *